Written by Max Gopfert – The collective failure of governments, NGOs, and the private sector across the world means that there are still 1.2 billion people living without grid electricity. With notable exceptions, grid connectivity is growing at a sluggish pace – and in some areas is worsening – as population growth outpaces connectivity. Sub-Saharan Africa has seen its off-grid population grow by more than 200M since 1990.

It is no surprise, then, that alternative, off-grid solutions have developed. The most successful of these has been solar lanterns: these are small, single lights that cost around $10 and are sold for cash. Propelled by simple economics (customers stand to save significant sums on alternative fuels over the lifetime of a lantern) and a population impatient to adopt modern technology, this market has boomed during the past five years. Cumulative sales have exceeded more than 50M products, and approximately 10% of the world’s off-grid population now have access to light from solar lanterns at home.

This is a huge success and should be celebrated. However, at Bboxx we believe that an important nuance is often overlooked. Solar lanterns have enabled energy access for millions, but have not necessarily relieved energy poverty. Imagine a world in which there is access to electricity, but only for your lights: that means no television, radio or other ‘basic’ appliances and services. Light, although important, is just one of the electrical-powered services that the 21st Century household, whether European, Asian or African, needs.

Solar products that offer sufficient capacity to meet the wider energy needs of the off-grid population at an affordable price do have the potential to solve energy poverty. They are also well placed to become part of the long-term energy infrastructure.

Solar lanterns don’t solve energy poverty

At Bboxx, we define a household as being in energy poverty if they lack access to sufficient energy to power the domestic appliances and services that they i) want and ii) can afford, when they want to use them.

There are many appliances and services that people may want but can’t afford, such as air-conditioning units or fridges. Being unable to power such appliances does not mean that a household is in energy poverty. On the other hand, a household that wants, and can afford, a television -but is unable to power it – is in energy poverty.

A good test for both of these factors is to compare an off-grid household with an equivalent on-grid household. For example, if the typical Rwandan farmer with reliable on-grid electricity has a television and four lights, then an off-grid Rwandan farmer of comparable income is in energy poverty if there is no access to sufficient energy to power a television and four lights.

Having access to sufficient energy to power such appliances when you want to use them is important. A household is still in energy poverty if they have a light but lack power during the evening hours when they need it, or if they have a television but only enough power for 30 minutes when they want to watch their team play football.

For these reasons, many customers of solar lanterns are still in energy poverty. They now have light, but like their grid-connected peers, many want, and can afford, lights in every room. Many want to power televisions and entertainment services, radios and fans, phone chargers and hair clippers. The better-off may even want to power fridges, tablets or other appliances.

Solar products can solve energy poverty, if they have sufficient capacity and are affordable

Solar products can relieve energy poverty in many cases. But to do so, two conditions need to be met.

First, they need to have sufficient capacity to power the appliances and services that the typical off-grid household wants and can afford. The capacity of a solar product is equivalent to the total appliances and services that it can support, multiplied by the hours of use it can power without interruption. This is most simply expressed in the energy consumption unit of Watt-hours (Wh). Powering four lights for five hours consumes around 20Wh, while running a television for five hours consumes around 50Wh. The capacity required to relieve energy poverty will vary by context (see later), but in general a capacity of 50-100Wh per day is needed to meet the energy needs of typical off-grid households.

Second, they need be affordable. The world’s off grid population are some of the poorest, and are highly price sensitive. A household only has ‘access’ to electricity if they can afford it. To relieve energy poverty for the off-grid population, the products have to be affordable for them.

Most solar products sold today do not meet these two criteria. The vast majority have a capacity of less than 20Wh, enough to support lights and phone charging. Where these products are used to power additional appliances, customers are frustrated by the limited hours of usage. Such products play a great role in helping the poorest households that are unable to afford more than these basic services, but many households still have unmet energy needs.

Larger solar home systems, on the other hand, can meet both of these conditions. With a capacity of 50+ Wh per day, they can support a range of appliances such as torches, radios, shavers, televisions and satellite decoders. To make them affordable, they are often sold as a service or on credit, with affordable monthly payments as low as $5. This combination of capacity and affordability means that they have the potential to relieve energy poverty for large portions of the off-grid population.

Solving energy poverty means different things in different places

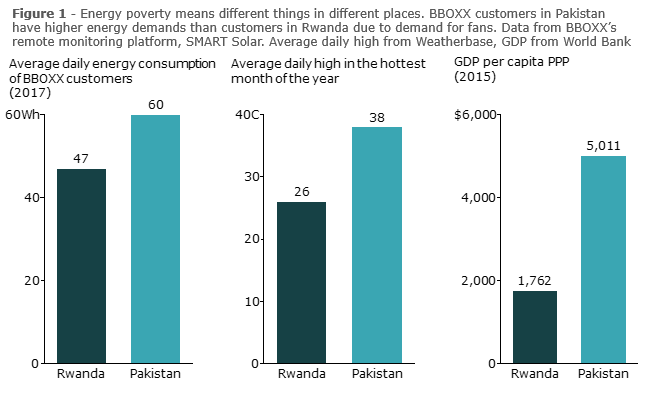

The minimum capacity required for a solar product to relieve energy poverty will vary by context. Households in wealthier countries want and can afford larger domestic appliances that require more energy. Similarly, very hot countries, where cooling appliances (e.g. fans) are one of the first requirements, have higher energy demands. By contrast, poorer countries or those with more temperate climates have much lower energy demands.

For example, customers of Bboxx’s bPower50 in Rwanda use 20% less energy than customers in Pakistan. Pakistan is wealthier and hotter than Rwanda, and the main reason for the different energy consumption patterns is the additional demand from Pakistani customers to power fans and cooling appliances.

This means that the capacity required for solar products to relieve energy poverty will vary by context. Based on Bboxx data, in Rwanda a solar product needs a minimum capacity of around 50Wh to meet the energy needs of the typical off-grid household, while in Pakistan this is 60Wh. In other countries or regions this may be even higher. Much of Latin America, for example, is wealthier than both Rwanda and Pakistan.

The grid is not always the best option to relieve energy poverty

For large portions of the off-grid population, connecting to the grid is the best option to relieve energy poverty. Although larger solar products can meet users’ energy demands, the grid usually provides the most power at the most affordable price. But this is not always the case.

First, in many remote areas, the grid is too unreliable. Grid outages in some Sub-Saharan African countries can reach up to 12 hours per day, meaning that many people with grid connections still lack access to sufficient energy to power their domestic appliances and services. This unreliability is also linked to serious dangers: power surges can cause fires and shocks.

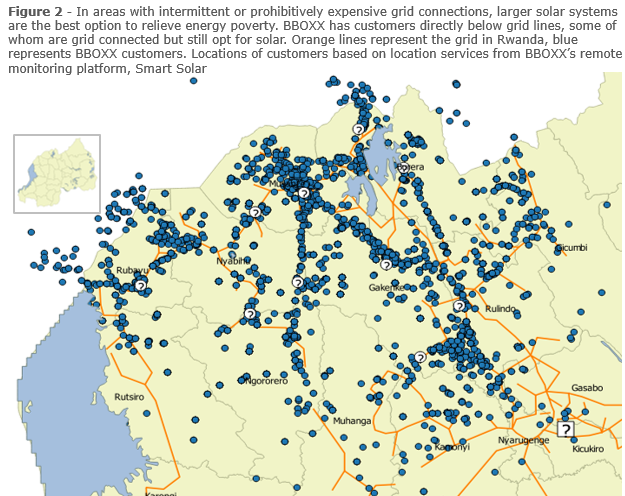

Second, despite an affordable unit cost for grid electricity, the upfront connection cost can be too expensive for off-grid households to afford. Even in one of the most progressive Sub-Saharan African countries, Rwanda, the cost of connecting to the grid is around $70 – equivalent to a typical off-grid household’s monthly income. This means that grid-connected areas can still have low electrification rates.

The result is that, in many grid-connected areas, larger solar home systems are the best option available. They meet customers’ energy needs, are safe, reliable and, with an upfront cost of $5-10, affordable. The best evidence for this comes from the operations of solar companies in areas with grid connection. Many households close to power lines, or even those with a grid connection, will opt for solar products over the grid. This suggests that in such areas, larger solar home systems stand to become a permanent part of the distribution mix in the future.

In conclusion, solar lanterns have provided light to hundreds of millions of people. But light is not electrification. To electrify those living off the grid and relieve them from energy poverty, solar products need to offer sufficient capacity at an affordable price to meet off-grid households’ energy needs. This will vary by context, but our data suggest a minimum capacity of 50-60Wh per day is required to relieve the typical off-grid household from energy poverty. Solar products that meet these conditions can even compete with the grid and will become a permanent part of the future energy infrastructure.